Slow-moving justice for Police Officers who commit criminal acts seems to be the norm in El Paso.

7 April 2024 (El Paso, Texas) Steven Zimmerman

Let’s talk about an officer who is charged with rape and should be charged with stalking.

There is a thin blue line that protects police officers. It’s necessary protection as many see the police as a pariah feeding off of the citizens they are meant to protect. Far too often, good cops can’t catch a break because of that belief, or they are blamed for the actions of others.

“We’re talking, people are talking,” says an officer who phoned me early this morning. “People are finally starting to see what we face when the system breaks down.”

This officer called me because an officer, even I forgot, was arrested last year for sexual assault.

On 7 July 2023, Special Investigation Unit officer Guadalupe Sosa was arrested on allegations that he raped a woman in April 2018 while he was off duty.

The Special Investigations Unit is the same unit that has harassed my family for nothing more than my writing articles critical of the police.

“Sosa has charges of sexual assault,” says the officer I spoke to, “but also was running people and getting information off our computers. He was looking up other people, and that goes on a lot here.”

For Sosa, that’s not the only charge he’s had. Also, in June of 2023, Sosa used his badge as a gateway to look up information on the department’s database. The information he accessed was not part of a case he was working on.

In Officer Sosa, we have a three-pronged problem: sexual assault, running people on police computers, and court cases that are taking longer than they should.

Sexual Assault and the Badge

Sexual assault is a very traumatic experience for anyone. When justice moves slowly, as it often does when police officers are the perpetrators, the system unwittingly revictimizes the one who was attacked.

Within our judicial system, there is the belief that you are innocent until proven guilty. In the case of Sosa, there was enough evidence obtained to support the allegations of sexual assault.

Abbott replied: “Rape is a crime, and Texas will work tirelessly to make sure we eliminate all rapists from the streets of Texas by aggressively going out and arresting them and prosecuting them and getting them off the streets. So goal no. 1 in the state of Texas is to eliminate rape so that no woman, no person, will be a victim of rape.”

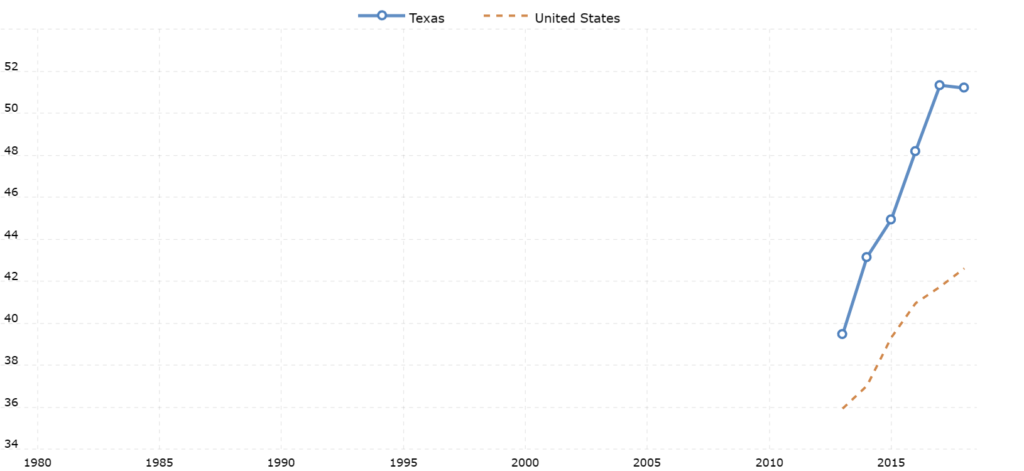

Governor Abbott’s comment comes from 2022 when Texas led the United States in cases of rape. When Sosa is alleged to have raped a woman in 2018, the number of rapes reported in Texas was 51.19 per 100,000 people.

Six years later, Sosa’s rape case is still moving slowly through the court system.

“It is often said that victims of sexual assault are victimized twice, once by the perpetrator and again by the criminal justice system during the investigation of the crime and, if a suspect is arrested, during the prosecution phase.” (Bartol & Bartol, 2017).

That sense of revictimization is worse when the assailant is a police officer.

“Fear, terror, anger, grief, trauma, these are just some of the rollercoaster of emotions and feelings one suffers through after sexual assault,” says Dr. Greenberg, a psychologist who specializes in sexual trauma. “Those feelings are expo notionally multiplied when the assailant is a police officer who has sworn to uphold the law.”

Dr. Greenberg said that one of the chief legal tactics when an officer is the alleged rapist is time.

“The further one is from the crime, the further one is from the arrest, the further one is from the last time the general public last read or heard about the rape, the better for the officer,” says Dr. Greenberg. “Time gives the defense a way to say, ‘Your honor, even though my client is a law enforcement officer, there is no public outrage.’ That often results in dismissals or reduction in the charge.”

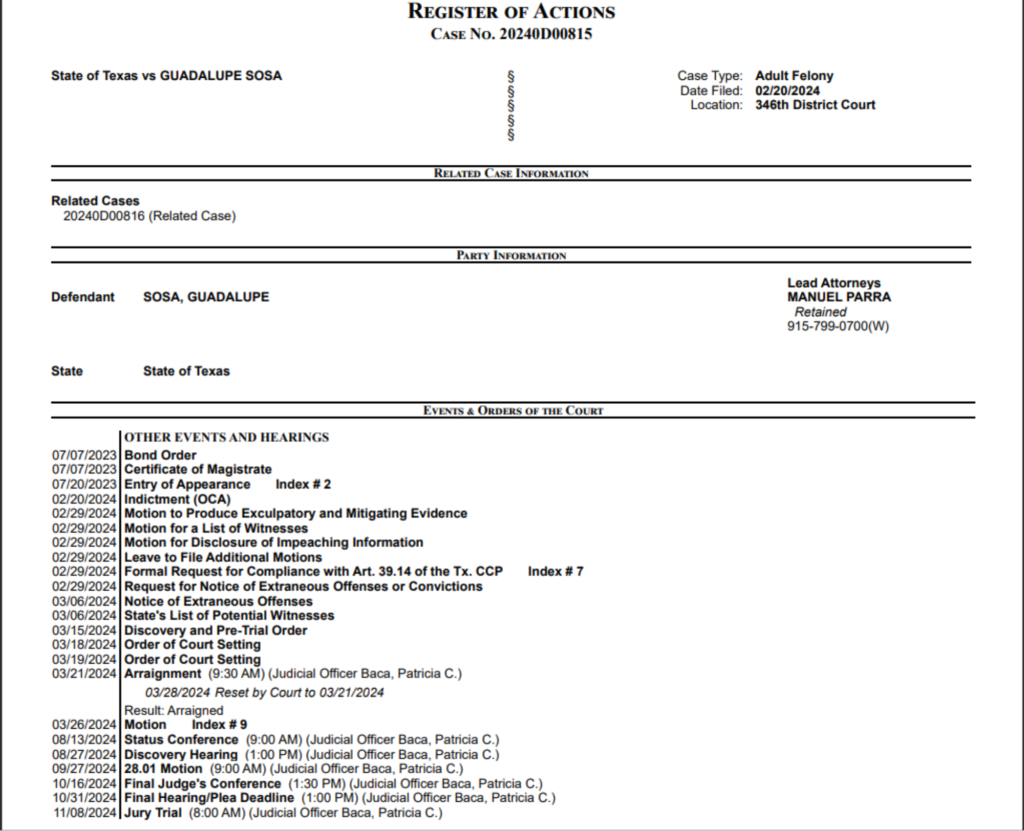

Sosa’s next hearing is a status conference on 13 August 2024 at 0900 in Judge Patricia Baca’s court.

08/13/2024 Status Conference (9:00 AM) (Judicial Officer Baca)

08/27/2024 Discovery Hearing (1:00 PM) (Judicial Officer Baca)

09/27/2024 28.01 Motion (9:00 AM) (Judicial Officer Baca)

10/16/2024 Final Judge’s Conference (1:30 PM) (Judicial Officer Baca)

10/31/2024 Final Hearing/Plea Deadline (1:00 PM) (Judicial Officer Baca)

11/08/2024 Jury Trial (8:00 AM) (Judicial Officer Baca)

Like Guadalupe Sosa’s booking and release from the El Paso County Detention Facility was fast-tracked, why isn’t his case?

Officer Sosa, a Stalker?

“We have a public trust,” says a detective with the El Paso Police Department, “and that trust is broken when an officer logs onto NCIC or TCIC and access records for personal use, as Sosa is believed to have done.”

Officer Guadalupe Sosa was walking around El Paso, I imagine, when he saw an ex-girlfriend with another man. Sosa then looked everyone up when he went to work the next day.

Like many officers, Sosa seems to think that confidential law enforcement databases like Facebook can be used for personal gain.

“On the systems we have access to,” says the detective, “officers like Sosa can find information on ex-girlfriends, neighbors, someone they thought was attractive, or how SIU is using the same system to find your family and harass them.”

The system police can access, and the information about people they contact are essential tools. However, when officers exploit the system for personal conflicts or voyeuristic curiosity to sidestep policies and the law, we, as citizens, can do little about it.

In Sosa’s case, he had no legitimate use in looking up an ex-girlfriend and the man he saw her with. He wasn’t pursuing a case against either of them, or he would have to remove himself from that case if he were. No, this was just outright cyberstalking, a crime he’s not yet charged with.

“It has all your personal information, everything about you,” says Mary Osborn, a woman whose ex-boyfriend, a police officer in Texas, pled guilty to a stalking charge. “When police access all your information like this, and it’s not for a case, they commit a crime against you. They look you up only to stalk you, follow you, harass you, or G-d knows what else.”

What Can Be Done?

The El Paso Police Department has a problem. One that I’m no longer sure can be solved. There is a level of corruption that needs to be investigated and removed. That corruption taints the officers who are there for altruistic purposes.

“This department has three different classes of officers,” says one officer I spoke to for this article. “You have administration, which is what you would call top-heavy. When was the last time the Chief had to patrol the streets? Then you have the ones who should not be cops, about a third. Then there are those of us who take the heat because of administration and the bad actors with a badge.”

The PIOs (Public Information Officers) claim the department embraces transparency. That is nothing more than lip service and a dream. Transparency should also include regular updates on where an officer is within legal proceedings and status updates on their cases after arrest. That would be transparency.

Far too many officers have “monolithic” and warrior visions of themselves. They are there for ego. They are there because they were bullied in high school. Once they pin that badge on for the first time and start their first tour of duty, others begin to characterize the civilians with hostility and gain a hypervigilant skepticism towards outsiders.

We need to codify transparency, what it is, and how a department can ultimately be transparent into law. If officers are breaking the law or engaging in misconduct, we need to be able to discover it. It should not be a secret that we must bow down to a self-serving PIO officer to reveal.

What can be done? Citizens can unite with those officers who want to better the department and the community and demand that the El Paso Police Department be more open and transparent, and officers such as Lt. Surface and Sgt. Adan Chavez, who was accused of sexual harassment, be terminated.

At the time of writing this article, it appears that the El Paso Police Department has terminated Officer Guadalupe Sosa.

Do you have a news tip or a story you would like to share? Click here to contact us.

Follow the Jerusalem Press on Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Threads | TikTok

While you are here, please take a moment to consider supporting independent Jewish Media. We do not hide our articles behind paywalls or subscription fees. Click here to support us on Patreon.